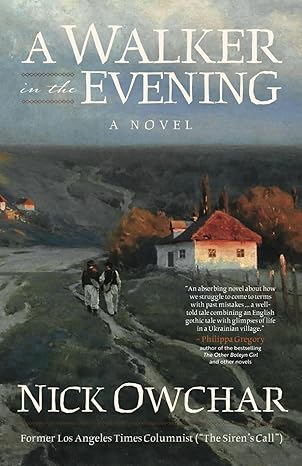

Today’s writers and editors have to be adaptable, and prepared for constant change. Nick Owchar, author of the new novel A Walker in the Evening, has long demonstrated these prized abilities.

For more than sixteen years, (1996-2012), Nick was Deputy Editor for Books (both literary and the publishing business), for the Los Angeles Times. He then moved into the writing/editing/content side of academia, first for Claremont McKenna College (his alma mater), then as Director of Communications for Claremont Graduate University, and since September 2022 as Editorial Director of Pitzer College, also part of The Claremont Colleges, in Southern California.

He also started his own company, Impressive Content, providing a variety of editorial services to authors and organizations, and writes for the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere.

I first came into contact with Nick in 2017, where his role at CGU included working with the Drucker School of Management. We first met in person at the Drucker School when I was there for Drucker Day in 2019. A few years later, we were both on a panel, “New Approaches to Proposals: Learn How Newsrooms and Magazine Editorial Departments Write to a Deadline,” for the APMP Western Region 2022 Conference, in Anaheim. And it was great to have coffee with him a month ago when I spent several days at the Drucker School.

I’m grateful to Nick for answering my questions about his new book, especially about his research and thought process behind the approach he took.

Kirkus Reviews and Philippa Gregory (author of The Other Boleyn Girl and The White Queen), both use the term “gothic” to describe your new book, A Walker in the Evening. In the context of the book, how would you define gothic, and could it also be called a historical novel?

When I think about what makes a novel gothic, I think about the feeling I had stepping inside the thousand-year-old Monastery of the Caves, which is where a bunch of orthodox monks and mystics are buried in Kiev.

There was so much to see, but it was hard to take it all in right away. The lighting was really bad—I think the whole place relied on candle power—and the monastery’s interior was lost in shadows. Once my eyes adjusted, though, I finally started noticing alcoves and arches, statues and interesting mosaics. There were gloomy corridors that took you all around the monastery. When I thought our tour was over, we were taken down some steps that led to a whole subterranean system of caves where the monks are buried. I was stunned. While we were walking around the monastery, I had no idea that there was so much hidden beneath our feet.

I think gothic novels function like that. They’re all about creating a gradual awareness of a mystery. There are layers and levels. The reader enters the story and is given a few ideas, but it’s not enough to see clearly.

In my book’s case, things start out simply enough—with a man leaving his house to walk around his village. His wife is mad at him for some reason, and he needs time to sort out a proper response. But he’s also carrying a strange wood object that begs for an explanation, and the fact that he’s an Englishman living in a poor Ukrainian village begs for an explanation, too. Gradually, as this man (our narrator) reflects on his life, the reader learns who he is and how he got there—and it was really satisfying for me to see how it would all play out.

Gothic novels usually have some supernatural element, too. I can point to two sources for mine: the eccentricities of the painter-poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Ukrainian village customs. Rossetti is an important character in my book: the narrator encounters him near the end of his life when he was sick, depressed, and convinced his dead wife was haunting him. And the village customs and folklore of Prehovinka come straight from my father, who was born in what would later become part of modern-day Ukraine. His village was as rich in lore and superstitions as a collection of tales by the Brothers Grimm.

Can you describe your research (especially as the story takes place in two countries), and what your thought process was in setting it in both the 19th and early 20th centuries?

I read a great deal about Victorian England and about the lives of Rossetti, Algernon Charles Swinburne, and other members of their circles. I found several contemporary accounts—especially a memoir by Ford Madox Ford—that were incredibly helpful in capturing a sense of the parties and the day-to-day experiences of London’s cultural elite. For the novel’s Ukrainian village framework, my research was aided by the terrific scholarship of historians including Orest Subtelny and Norman Davies (Davies is a real master in establishing historical context).

But—and I really need to stress this—I also had a unique source. As I mentioned before, my father was born and raised in Western Ukraine. He told me so many stories about life there that seemed wild and strange—especially about the totem with a devil’s face and the fact that every village family had to patrol the village from dusk to dawn.

We talked about his experiences constantly, and by the time we visited there in the late 1990s, I had this incredible feeling of déjà vu. It’s pretty amazing to enter an unfamiliar place in another country and know where things are. The narrator explains to someone that the village of Prehovinka is a part of him because of blood, because of his father, and that comes from me.

I think some scholars of Ukrainian village life could pick out anachronisms in my story that don’t agree with their research, but I don’t care. I added an author’s note to the book where I explain that staying true to my father’s stories was more important to me than winning the approval of a scholar (even if that person turned out to be Davies!).

In the course of writing and creating characters, were you, perhaps in the back of your mind, thinking cinematically, including how these characters might look and act onscreen?

Totally. I don’t think it’s possible not to think in cinematic terms, especially if you’re a binge watcher of Netflix (which is true of my wife and me). You see (and read) so many stories where a character looks back on some damaging situation from the past. It’s a good formula, and my story uses it.

But I had no idea I was going to organize it this way when I started. For a long time, in fact, I’d hit a brick wall with my novel’s structure. I had created a generic gothic novel, and my agent was having troubling selling it. She kept coming back to me with suggestions that might make it more marketable, and it was too much. She was only doing her job, but it messed me up. I tried a bunch of different angles and created a lot of new material (I’ve never had a problem with writer’s block), and I finally had to stop. I was overwhelmed. It was my wife who sagely advised me, as she does in everything, to put it aside until I was ready to try again.

In the meantime, something important happened. We had a garage sale.

When we were cleaning out our garage, I found a box of reporter notebooks and cassette tapes from my interviews with my father. I also found my travel journal from our Ukraine trip, and it changed everything. It didn’t take long to realize I needed a frame narrative in the village. In some works of fiction, that frame is just a narrative device to help get the story off the ground, but mine is more than that. It’s full of color and incidents that I think my father would recognize. I’m really proud of that.

I’ve never been more grateful for a garage sale. To anyone with a novel in progress, all I can say is, be open to the unexpected: You can never tell where the right inspiration is going to come from.